How the federal government’s carbon pricing plan may impact the ag industry.

Members of the agriculture community are divided over the federal government’s upcoming carbon pricing plan. Some are unsure and hesitant, some are vocally against it and there are those who have openly embraced it.

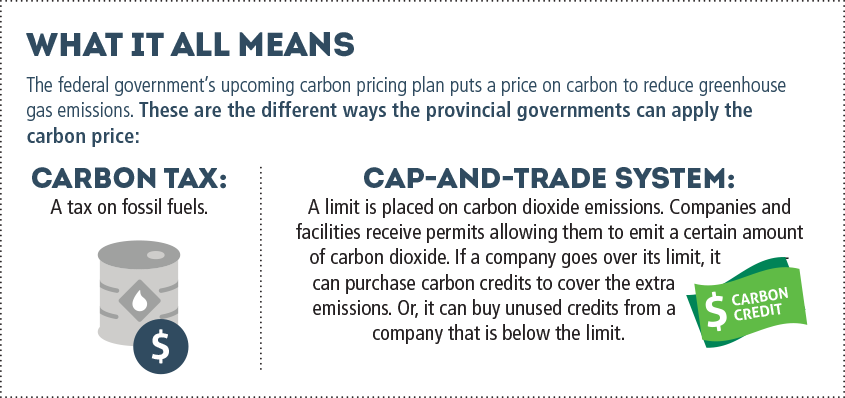

This plan, announced to the House of Commons on Oct. 3, 2016, states that all provinces must adopt a carbon pricing plan or a cap-and-trade system by 2018. If a system isn’t implemented by 2018, the federal government will assign one. The provinces’ benchmark carbon pricing plans must meet the government’s benchmark price. The price for carbon dioxide emissions will start at $10/tonne in 2018, and will rise to $50/tonne by 2022.

British Columbia and Alberta already have their own carbon tax plans. British Columbia’s was launched in 2008, and is currently pricing carbon emissions at $30/tonne. Alberta’s began on Jan. 1, 2017, and started at $20/tonne, and will rise to $30/tonne by 2018. Both plans apply to gasoline, diesel, natural gas and propane.

Estimating the Impact

Kevin Hursh, owner of Hursh Consulting & Communications Inc., says there’s a feeling of trepidation among producers about carbon pricing. There are exemptions and rebates available in Alberta’s plan, but Hursh says rebating farm fuel only goes part way, and doesn’t address extra costs for the transportation and production of ag fertilizer and chemicals.

“So, as a result, we’ve got a whole lot of estimates and guesstimates as to how much carbon pricing may cost producers and frankly, I don’t think anyone knows at this point,” says Hursh, adding there are many views about whether or not this is the most effective way to reduce carbon emissions.

If other major competitors around the world — particularly the U.S. — do not have a similar carbon pricing regime, then we better be careful.

“Economic theory would say that increasing the price of something reduces consumption,” he explains. “However, farmers have very little ability to switch production practices and do things differently and save many — or any — of those emissions.”

Retailers and producers are still going to need those inputs, says Hursh, but the health of the entire industry could be compromised if Canadian ag is uncompetitive and our crop production cost structure is too high.

“That, in turn, affects the entire agricultural industry,” he says. “Retailers will have no choice but to pass along — the best they can — the cost increases that come with carbon taxes, carbon pricing and the layer of carbon pricing from production of inputs to transportation of inputs. They’ll have no other way of doing business other than to try and pass along those cost increases.”

According to Hursh, there could be different implications from one province to another depending upon how carbon pricing is implemented. Hursh says the big worry is that carbon pricing could make Canadian producers and retailers uncompetitive with other countries.

“If other major competitors around the world — particularly the U.S. — do not have a similar carbon pricing regime, then we better be careful,” he says. “Because we could make ourselves uncompetitive with other nations, such as the U.S.”

Not only that, but he says the plan may lead Canadian producers to circumvent the pricing by getting inputs from American suppliers that aren’t affected by the same taxes.

Staying Sustainable

If the purpose of carbon pricing is to encourage people to change the way they do things to combat climate change, agri-retailers and producers should be recognized for the environmentally-friendly practices they are already using, says Robin Speer, executive director of the Western Canadian Wheat Growers Association.

These positive outcomes have been occurring without carbon taxes and they’re going to continue.

“Farmers have been doing all these great things for over 25 years, even going back further than that — using practices like no-till agriculture, modern precision farming and modern crop protection products,” says Speer. “Of course, yields are increasing, which means even more carbon is sequestered in the soil, and that’s a positive story. It’s one thing to tax fuel and fertilizer if they’re emissions-intense, but if from a public policy perspective you want to reduce carbon — and western farmers are reducing carbon on a full life cycle basis — it would be a perverse decision to tax the inputs on the front end and not realize the overall positive impact on outputs on the back end at harvest.”

Speer says environmentally-friendly agriculture practices will continue regardless of the carbon pricing plan that is introduced, since the industry is always looking for ways to reduce fuel and fertilizer use where it makes economic sense.

“This is all happening because it makes good sense. It’s good for the profitability of producers and it’s good for sustainability,” he says. “These positive outcomes have been occurring without carbon taxes and they’re going to continue. Farmers want to burn less fuel, they want to use less fertilizer, they don’t want to pay for those inputs. And at the same time, they want to keep their soil healthy for years and years to come.

“I think if people want to regulate and tax us at various levels of government, they need to understand the story of where we were and where we are — it’s good news.”

The Other Side of the Coin

Alastair Handley, president and board member of Carbon Credit Solutions Inc., says that pricing carbon is effective when done through a carbon market, rather than through a carbon tax. Carbon markets can be beneficial for the industry and the environment in the long run, he says. He also adds that these markets can provide a new revenue stream for producers that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by practicing no-till farming through direct seeding.

Handley says it’s very easy to focus on the negative stories surrounding carbon taxes, like the effect on the economy and retailers and the potential costs. “It’s much more interesting, though, to look at the opportunities that carbon markets present, because that’s what we want to take advantage of,” he says. “There are opportunities to generate revenue from these markets.”

Growers in Alberta have been taking advantage of its carbon market for the last decade. While Alberta implemented their carbon tax earlier this year, the province has had a price on carbon credits since 2007, which has been applied through a carbon market. Alberta’s carbon market requires companies that emit more than 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year to reduce emissions in Alberta, according to Handley.

“You can invest in your facility and reduce emissions that way, or you can pay somebody somewhere else in Alberta to reduce those emissions, which you take ownership of,” he says. “You’re paying somebody to reduce emissions on your behalf within the province of Alberta.”

Alberta’s market, like Ontario and Quebec’s cap-and-trade systems, allows polluters to use carbon credits to help them meet their legally enforced compliance obligations. Since 2007, grain growers in Alberta that have participated in the market have earned more than $100 million for their carbon credits. This market still exists and the carbon credits are generating increasing revenue streams for growers.

Handley says that the federal government’s carbon pricing plan allows provincial governments to create a carbon market, implement a carbon tax or do both, and adds that a well-run carbon market can provide growers with a new revenue stream.

Executing the Plan

Revenue is the word that most people are concerned with. Is carbon pricing really intended to combat climate change, or is it just another tax? One big question looms over the proposed plan: where will the revenue go?

The federal government’s plan is a national one, but is being implemented at the provincial level. The revenue generated in each province will remain with that provincial government.

“The actual implications may differ from province-to-province; and I would say the opportunities to profit from the carbon price will differ from province-to-province as well,” says Handley.

If the provinces apply the revenue to beneficial practices in the industry, Hursh says that has the potential to make a difference and reduce emissions. He believes that creating an incentive to use nitrogen-stabilizing products would make “a lot of sense.”

“If you’re using a granular nitrogen fertilizer, one of your biggest losses could be volatilization,” he says. “Products are available that reduce the volatilization and the loss of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide is one of the worst greenhouse gases — far worse than carbon dioxide.”

If the revenue generated from the plan was used to incent producers to buy nitrogen stabilizers, Hursh says there would be more nitrogen available to the growing crop and less nitrogen gassing off in the atmosphere.

“You would have a measurable result in what you’re doing for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. I think a big part of the success of carbon pricing will be what governments decide to do with the money collected, and how they will apply that to get us to where we want to be in terms of reducing emissions,” he says.

Hear more from Kevin Hursh at the CAAR Conference.

Understanding Farmer Motivation: Wednesday, Feb. 15, 10:30 – 11:30 a.m.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

Join the discussion...

You must be logged in as a CAAR member to comment.

Report

My comments