By Shaun Holt, Chief Executive Officer, Alveo Technologies, Inc.

Just as pathogens mutate, so does science advance to combat them. Sometimes, we can find a cure and eliminate it; other times, we devise an early-warning system to protect the herd or crop yield and, thus, the farm business. Sometimes, all one can do is find a way to endure.

Regardless of how or what, the goal remains to protect.

Even with the calendar flipping to 2024, the poultry industry is still experiencing a global crisis due to a devastating pandemic.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has killed and required the slaughter of hundreds of millions of domestic fowl, causing billions of dollars in damage and disrupting trade. According to the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the virus has affected about 70 million birds, breaking a record previously set in 2015, which had seen some $4 billion in economic damage.

Recent outbreaks in California and Alabama required the culling of nearly 700,000 birds.

But while HPAI is the most visible disease affecting agriculture, other livestock and crops are in danger.

According to a 2021 study presented in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [of the United States of America]), one of the world’s most-cited and comprehensive multidisciplinary scientific journals, publishing more than 3,500 research papers annually, “Plant diseases, both endemic and recently emerging, are spreading and exacerbated by climate change, transmission with global food trade networks, pathogen spillover, and evolution of new pathogen lineages.”

In other words, the risk of emerging new agricultural pandemics is growing larger daily.

What can the ag sector do about it? The first line of defence is testing.

You can’t treat diseases you can’t identify. Farmers and authorities need to know quickly and reliably what is killing their animals and crops to contain the damage quickly.

The most common type of test is a lab-based polymerase chain reaction, better known as PCR, a test we all became very familiar with during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For a PCR test, a sample must be collected, protected, and shipped to a lab where genetic material will be heated and cooled for many cycles. The test is precise, but getting a result can take days or weeks if the test lab is over capacity, as it will likely be during a serious outbreak.

Can farmers wait days or weeks to contain a problem when every precious moment means greater loss of animals, crops, and profit?

Of course not.

But there are solutions.

For example, lateral flow tests (LFTs).

More commonly known as antigen tests, LFTs don’t typically require a lab to get a result. For most LFTs, tests can be performed in the field, and results are obvious soon after. Unfortunately, LFTs are not as sensitive as PCR. They also provide a significant number of false negatives, which is why experts recommend conducting multiple tests over extended periods of time if the first test is negative.

Let’s take HPAI as an example of why these two common types of tests aren’t meeting the challenge of the current pandemic.

HPAI kills and spreads quickly. In 48 hours after the first bird shows symptoms, an entire flock of thousands can die. Also, while HPAI doesn’t spread easily between humans, there have been around 250 documented cases, most of which were people catching it after exposure to infected birds.

In 56 percent of these bird-to-bird HPAI cases, the disease was fatal.

So, when farmers wait days to get results or get results that falsely say their birds are clear, the virus has more time to spread farther into the flock and prolongs the exposure to the people who work with the birds.

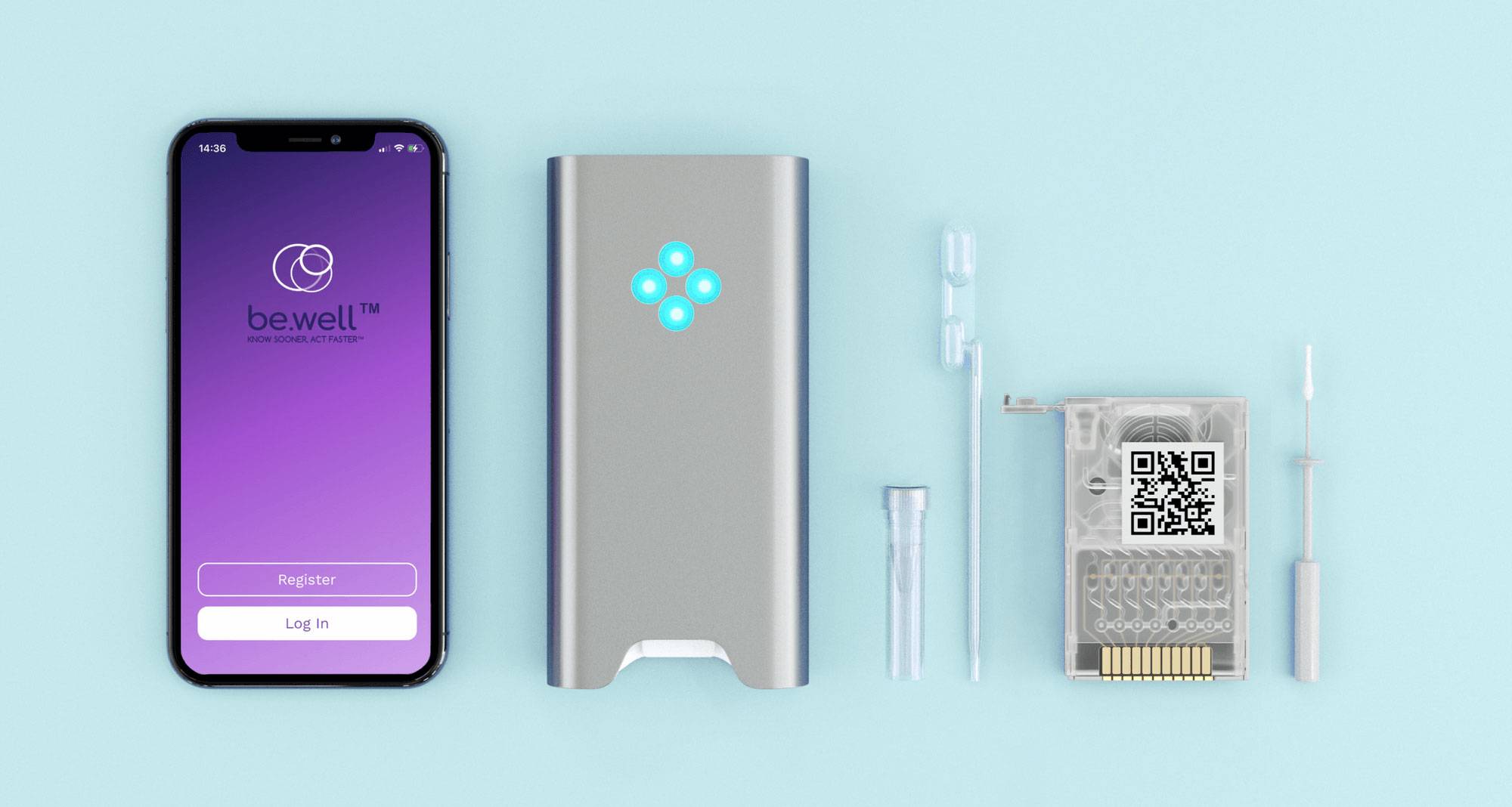

Agriculture needs tests that provide accurate results quickly in the field and can transmit results automatically to the relevant authorities.

Loop-mediate isothermal amplification (LAMP) is a DNA amplification technology similar to PCR, but the key difference is that it holds the sample at a steady temperature instead of cycling.

The LAMP technology has recently come off patent, and as a result, a great deal of innovation is taking place.

Rugged tests are in development for agricultural use that provide precise results in about 30 minutes. Some can automatically transmit geotagged results to the Cloud, which helps authorities stay ahead of the spread.

We live in a new era where emerging pathogens become more common, and aggressive efforts will be required to contain the damage to the industry. But to win in this fight against disease, we need a new testing paradigm.