By Andrew Joseph, Editor

July 2023 began with consecutive days of what has been described as being the hottest day the Earth has experienced since we humans began to measure such things.

On July 3, the average global temperature measured 17.01 Celsius (62.618 Fahrenheit)—a new record!

The previous record, according to the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer, was 16.92 C (62.46 F), set in August 2016.

If that temperature sounds quite comfortable, remember that this is an average global temperature and the overall number includes notoriously chilly spots like the Arctic and Antarctica.

It was broken, however, the very next day on July 4, when the average global temperature reached 17.18 C (62.92 F), and matched again on July 5, before the record was raised higher on July 6, with global temperatures hitting 17.23 C (63.01 F).

We should point out that the recording of these global temperatures only goes back to the 1940s, per the Copernicus Climate Change Service, but Jennifer Francis, a senior scientist with the Woodwell Climate Research Center, said these high temperatures may be the warmest the planet has seen in the past 100,000 years.

Although that may be a bit of soundbite hyperbole from Dr. Francis—there was a seven-year gap between the 2023 record-breaking temperatures and the previous high recorded in 2016—higher temperatures were possibly experienced even before humans began recording such data.

As of this writing, the average global temperature is expected to only rise or get worse through the next six weeks, which are July and most of August—July is typically the Earth’s hottest month.

Still, we should not discount Francis’ 100,000-year guesstimate (though why not say 250,000 years?) because scientists extract historical weather data from coral reefs, tree rings, and ice cores, denoting when things get, amongst other things, hotter—we aren’t precisely sure how hot things were.

We’re In A Drought

The average person visualizing a drought can conjure up some pretty arid conditions—and they would be correct.

In a water cycle, there are two main components. Precipitation adds water to the surface, while evapotranspiration (water loss from plants, bare soil, and bodies of water) removes water.

A drought occurs when there is a shortage of precipitation. It can be made worse by being unable to meet evaporative demand.

The term evaporative demand is a quantifiable number representing the potential water loss from the Earth’s surface driven by atmospheric factors such as temperature, wind speed, humidity, and cloud cover.

It’s a vicious circle. Periods of high evaporative demand are connected to droughts and increased fire danger—anyone with a functioning snoot will be able to recognize that the summer of 2023 had more than its fair share of fires, spreading the stench of burnt offerings across Canada and down into the US.

Droughts affect the more sensitive sectors of agriculture, including crops and livestock. They can also impact insects, diseases, soil quality, and yes, weeds—all of which affect livestock health and, when there are not enough ag products to feed us, the health of human beings, too.

Drought can cause billions of dollars worth of damage in Canada alone.

And, although one can adequately quantify it, a drought’s effect on one’s mental health is a concern. There’s also that suffering person’s mental health and its effects on family members and workers—all occurring when a drought hits a farm’s production.

According to researchers such as the Berkley Earth environmental data analysis group, the heat affecting most of the planet is caused by El Niño and the double whammy of greenhouse gas emissions.

El Niño, aka “The Boy”, is the warm phase of the ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation), the cycle of warm and cold sea surface temperatures in the tropical central and eastern parts of the Pacific Ocean. El Niño brings high air pressure in the western Pacific and low air pressure in the eastern Pacific.

You Can’t Predict A Drought

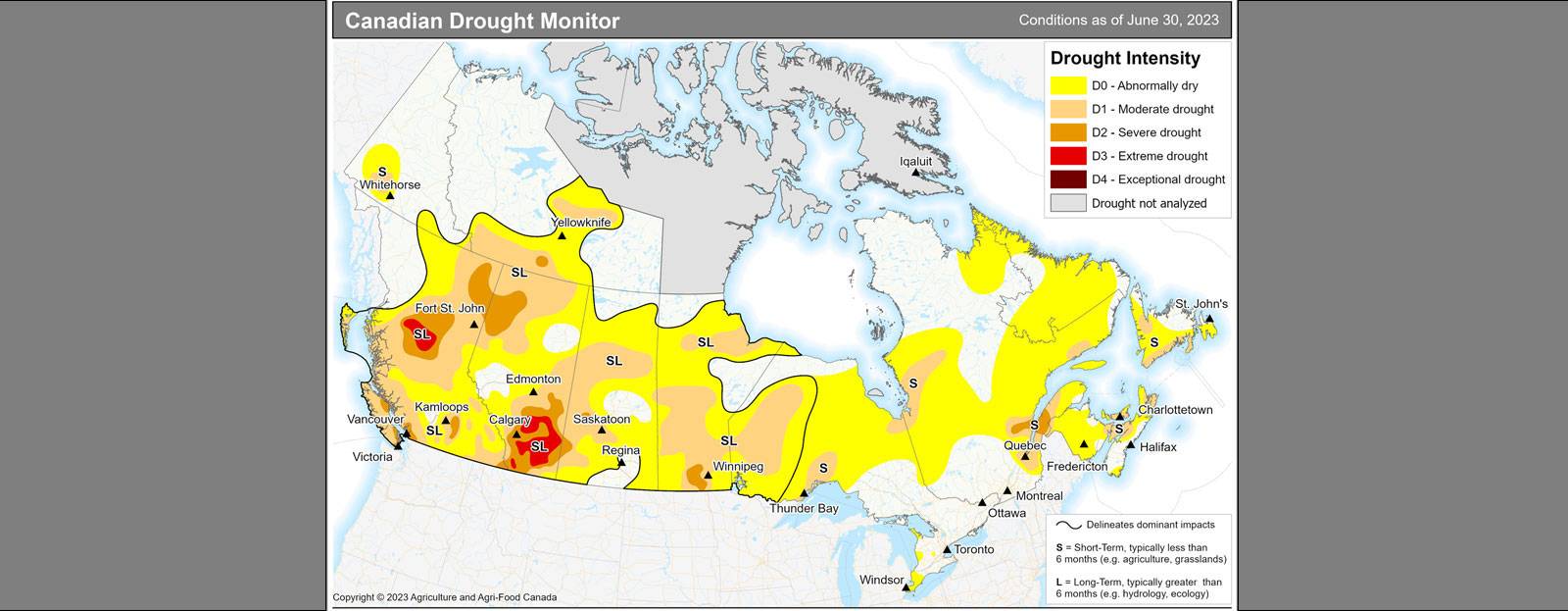

Canada, according to the Canadian Drought Monitor, is currently in a drought.

The writer looks at his weedy, green lawn and shrugs his shoulders—obviously not all of Canada, but certainly much of it—especially the west coast, Prairie provinces, and the east coast.

The most recent (as of this writing) Canadian drought map bears data as of June 30, 2023.

While much of Canada—right across all provinces and territories—is denoted as being exceptionally dry, there are a few larger areas (and growing) where we are in a full-scale drought.

Yukon may be the least affected, but no data was available for Nunavut. However, considering how drought within the Northwest Territories can be seen creeping along part of its shared border, we can extrapolate that Nunavut is getting dry as well.

Even southern Ontario is showing signs of drying out. Moderate, severe, and extreme droughts are all becoming part of the geological landscape in Canada.

Drought is challenging to predict because of its “creeping” characteristic of slowly developing but continuous, cumulative, and long-lasting effects. Although there is no single methodology for measuring drought, the Canadian Drought Monitor analyzes data regarding precipitation and temperature indicators, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index satellite imagery, streamflow values, the Palmer Drought Index, the Standardized Precipitation Index, and other drought indicators used by the agriculture, forestry, and water management sectors.

Drought negatively affects our Canadian ag-growing industry, though it is hardly a new phenomenon for us.

According to Climate Data Canada, we’ve suffered under at least 10 multi-year severe droughts in the past 113 years: 1910–11, 1914–15, 1917–20, 1928–30, 1931–32, 1936–38, 1948–51, 1960–62, 1988–89, and 2001–03.

In the examples above, the minimum length is two years, with the longest-lasting one being a four-year dry spell just after WWII.

Sometimes, the drought chiefly affects an area of the country, such as in 2015 when it hit British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan—an event partly attributed to climate change.

According to a 2004 report prepared for the Government of Alberta, the droughts of the 1980s and 1990s were comparable to the arid devastation seen in the severe droughts occurring in the 1920s and 1930s, the so-called dustbowl years.

You Can Predict A Drought

While the above heading directly contradicts the previous one, it is 100 percent correct—it is possible to predict a drought.

Although it is impossible for anyone to predict its volatility or precisely where it will hit, it is possible to predict when that drought will occur.

By analyzing the data surrounding crops impacted by the weather over the past century, we can use that data to predict what Mother Nature has in store.

It all comes down to the 89-year cycle, also known as the Benner Cycle.

Regardless of whether it’s a good or bad year, Dr. Taylor found that similar results occurred 89 years previously and a further 89 years before that.

Dr. Elwynn Taylor is a climatologist and agriculture meteorologist with Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa.

Not only was his data based on crop harvests since the 1800s, but Dr. Taylor also backed up his data with the physical evidence of tree rings.

Tree rings are wider apart in warm, wet years but are thinner in cold, dry years. When the stressful experience of a drought hits, a tree may not show any growth at all, instead expending its energy only to survive.

The Benner Cycle was created in 1885 by Samuel Benner (1832–1913), a prosperous farmer who was wiped out by the economic Panic of 1873 and wanted to learn what caused market fluctuations.

Relative to crops, he discovered that weather cycles were the cause, publishing his results in his book, Benner’s Prophecies.

Going back to data collected just before the 1800s, Benner determined the impact of the dry/wet weather cycle and then postulated through the year 2000 just what its impact would be.

Using the Benner Cycle, Dr. Taylor showed its predictive nature to be accurate, plus or minus one year. While an 89-year cycle spread over 220+ years is not irrefutable evidence of the process, Dr. Taylor’s research into weather and its effect on crops shows that he and Benner may be onto something tangible.

In his home State, Iowa, Dr. Taylor noted that between 1900 and 2000, there was an approximate 18-year cycle with a one-in-three chance of a drought for corn harvests. For the other years, the odds of a drought became one-in-12 or a one-in-13 chance.

Dr. Taylor pointed out that farmer Benner’s calculation pre-1900 showed that the average time between droughts was every 18.6 years.

Data from Dr. Taylor showed that weather volatility is likely to be more significant over the next 20 years across North America, and he cautioned farmers that risk management would be paramount to preventing disaster.

The Worst Is Yet To Come

Examining the historical aspect of the Benner Cycle, Dr. Taylor said that the worst part of the 89-year cycle occurred in 1846-7, followed by the so-called “Dust Bowl” years of 1935–6.

Following that 89-year cycle, Dr. Taylor suggested that the next most volatile year will begin in 2025—i.e., the worst year for crops in both the US and Canada will be in two years.

But what should we expect? Farmers in the 21st century are certainly better stewards of the land than their 19th and 20th-century counterparts, so there will not be a repeat of the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, when dry, dusty windstorms blew away the nutrient-rich topsoil from millions of acres of American farms in the central and southwestern interior.

That destroyed the livelihoods of farmers and migrant workers across Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma.

In Canada, we have less volatile drought conditions than in the US. Still, US farmers must work their soil more effectively than they did 90 years ago, so dust bowls will not happen again.

Canada suffered from drought in the 1930s, sure, but it was never as pathetic as it was in the US. It was just a matter of geography.

So, the bad news is that according to the Benner Cycle, we will remain in a drought pattern for a few more years, peaking in 2025 before slowly beginning to ebb.

Again, only some parts of the country will be badly affected. As seen in the Canadian Drought Monitor map (Page 5), some areas will be more affected than others.

What can be done? Some suggestions include cover cropping—using a plant mixed in with your regular crop to grow alongside it to slow erosion, improve soil health, enhance water availability, smother weeds, and help control pests and diseases.

By adding different plants with complementary root systems—shallow-rooted plants absorb water quickly; deep tap roots use subsoil water in dry conditions—it helps the soil retain more water when there’s less rain, preventing water runoff.

Other suggestions are to avoid soil compaction by always driving on the same soil route year after year. This allows the soil to aerate itself, allowing better water infiltration—no runoff due to compaction. The result is higher yields and even better grain quality.

The most obvious solution would be for farmers to have a reserve of water—hmm, how can an ag retailer help there? Reservoirs can be dug to capture subsurface waters and replenished yearly by melting snow or redirecting some waters from another water source.

But the best suggestion is to overwinter crops. By planting crops in the Fall, and harvesting by late Spring to mid-summer, farmers can avoid the hot, stupidly dry weather of July and August.

Some popular growing crops include: winter wheat, hairy vetch, red clover, chicory, and plantain.

Farmers could also install an irrigation system or utilize better drought-resistant crops. Seed producers are always developing something new in that regard.

Different options are available to farmers across Canada, and it is up to agri-retailers to help them find the best solution to, at the very least, ride out the drought.