By Andrew Joseph, Editor

It’s spring when crop farmers and retailers think profoundly about fertilizer—the type, the amount of application when to apply, and the cost of the fertilizer relative to its effectiveness. And yes, availability affects the fertilizer retailers can offer their farmer clients.

We could beat a horse to death and explain again that Russia’s war on Ukraine has caused a shortage of fertilizer, which in turn has increased the price of fertilizer around the globe. So even if you could get hold of what you needed, its cost was high, reaching a peak in May 2022.

Ukraine, Russia, and its ally Belarus were major fertilizer suppliers to farmers worldwide.

In 2020, pre-war Russia contributed 14 percent of the world’s urea and 11 percent of its phosphate. With Belarus, Russia delivered 41 percent of the global potash mined.

If a country had no moral qualms about buying and selling from Russia and Belarus, it would probably receive its fertilizer at a relaxed price point.

But for Canada, the US, and the hundreds of other countries that refused to do business with them, it meant a fertilizer shortage.

Now, Canada and the US aren’t slouches when it comes to producing fertilizer, and as such, they were able to make up the fertilizer shortages—quickly enough, though perhaps not quickly enough for those who bought high to ensure they had what they needed early in the planting season.

Although Canada’s ag industry and all other sectors are facing blowback from the federal government to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40 to 45 percent by 2030, we point out happily that there is no mandatory reduction of fertilizer being placed on farmers.

And the rest of the world noticed that, too.

Fertilizer Canada proudly states that the Canadian fertilizer industry contributes $23 billion annually and over 76,000 jobs.

Potash is Canada’s most important fertilizer economically. In 2022, Canada’s exports of potash doubled—more than doubled by 130.5 percent compared to 2021.

Unsurprisingly, Canada was by far the world’s leading potash producer in 2022, with a large amount produced in Alberta and Saskatchewan. The Canadian fertilizer manufacturing industry was valued at $7.6 billion in 2023.

Rabobank is a Dutch multinational banking and financial services company headquartered in Utrecht, Netherlands. It has offices worldwide, including corporate offices in Toronto.

Rabobank has forecast an increase of nearly five percent in total fertilizer consumption in 2024.

It was noted that with fertilizer prices at lower levels and affordability being more positive, the world’s farmers are expected to increase sales into 2024.

And that’s good news for every one of the Canadian fertilizer manufacturers.

Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia have been at war for over two years now, which has curtailed their fertilizer production and shipments. There were shortages even before COVID-19, and before that, when flooding affected Louisiana fertilizer production, global fertilizer shipments took a hit.

Canada’s fertilizer industry has smartly picked up the slack to provide fertilizer products for demanding customers worldwide.

In 2021, Canadian fertilizer producer Nutrien Ltd., for example, increased its potash production by almost one million tonnes because of market demand. In 2022, Nutrien also increased its potash and nitrogen production.

Although nitrogen and urea remain the industry’s largest products worldwide, phosphate also accounts for a significant portion of demand.

While demand for fertilizer in Canada corresponds to farmer hectarage seeded and farmer incomes—a function of global crop prices—global prices depend on the Canadian dollar’s strength (or weakness).

Looking at data compiled by the research department of Statista (www.statista.com), Wesfarmers ranked as the largest fertilizer company in the world as of January 1, 2024, at US$42.29 billion, with Nutrien ranking second at US$24.22 billion.

Wesfarmers is an Australian company that sells retail products, chemicals, and fertilizers. Wesfarmers is well-known for making a big splash in the Australian and New Zealand markets.

Nutrien is a Canadian company headquartered in Saskatoon, formed in 2018 when Calgary-based Agrium Inc. and PotashCorp (aka Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan) of Saskatoon merged. The company is one of the largest potash producers globally, with over 20 million metric tonnes of potassium chloride plant capacity at six Saskatchewan mines.

Nutrien also has two large phosphate mines situated in the US.

Statista said that in 2022, Nutrien’s revenues were approximately US$37.9 billion, noting that the company had been showing a growing trend over the past few years.

It is also the third-largest manufacturer of nitrogen fertilizer, following the American company CF Industries and the Norwegian chemical company Yara. Of course, Yara and CF Industries also have their own entities in Canada.

Canada’s fertilizer industry will continue to grow domestically and internationally, especially in the US, as COVID-19 fears ebb away.

Recently, we saw many farmers panic, buying any type of fertilizer they could get their hands on. This is why there was a run on animal waste, causing a shortage. It’s also why every retailer warned its customers to order early to ensure they were first in line to receive fertilizer rather than putting in a request as needed.

Although companies such as Nutrien could have picked up the slack and offered fertilizer as required, it also caused others to formulate their concepts of alternative fertilizer.

It is not just done in case there’s a shortage but rather as a green alternative to reduce GHG emissions.

Jiminy! That’s Cricket!

We saw industry-wide complaints from farmers when the April 2022 peak fertilizer pricing for anhydrous ammonia was over US$1,600 (CDN $2,171) a ton before falling to $1,152 (CDN $1,563) a ton on August 25, 2022.

As of February 2024, prices were even lower. MAP (monoammonium phosphate consists of phosphorus and nitrogen) had an average price of $809 (CDN $1,097) per ton, potash $509 (CDN $690)/ton, urea $527 (CDN $715)/ton, anhydrous $770 (CDN $1,044)/ton, UAN28 $334 (CDN $453)/ton, and UAN32 $390 (CDN $529)/ton.

Sure Source Commodities LLC (aka SureSource Agronomy) of Petrolia, Ontario, has developed a new fertilizer source that will make your conscience feel good—unless you love or hate insects.

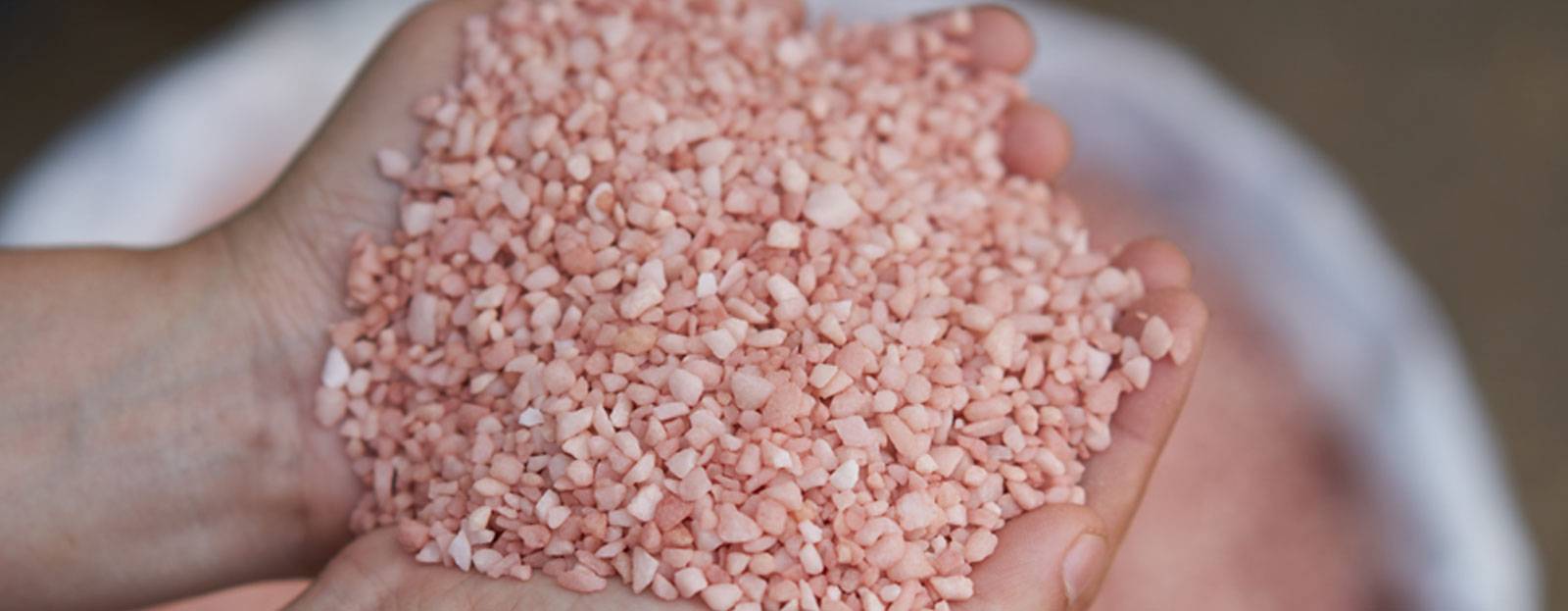

Featuring pelleted frass—that’s what the company calls the excrement, exoskeletons, and discarded feed materials of crickets—the Kickin’ Frass product received regulatory approval from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency on February 20, 2024.

SureSource said that cricket frass fertilizer provides growers with a sustainable fertilizer option that does not come at the cost of yield. SureSource takes pride in turning waste into something farmers can use to create healthier soil and healthy crops.

The crickets are cultivated on a state-of-the-art, closed-environment farm belonging to Aspire Food Group. The facility was designed for high-quality insect farming in London, Ontario. And while Aspire grows the crickets for food, the leftovers got SureSource thinking.

SureSource received a $200,000 Ontario grant in April 2023 as part of Bioenterprise Canada’s Fertilizer Accelerating Solutions and Technology Challenge.

Bioenterprise calls itself Canada’s food and agri-tech engine. It comprises a community of entrepreneurs, researchers, accelerators, and partners looking to drive Canadian innovation in our sector. Putting its money where its mouth is, Bioenterprise divvied up $2 million equally between the 10 Challenge winners, including SureSource.

The other nine winners were ALPINE, BioLiNE Corp., CanGrow Crop Solutions, CRF AgriTech LP, Escarpment Renewables, Haggerty AgRobotics, International Zeolite Corp., ReGenerate Biogas, and Woodrill Farms.

The Challenge’s goal was to “transition alternative fertilizer solutions from research and validation phases to successful commercialization and market entry.” With the funds in hand, SureSource met with the Vineland Research and Innovation Centre to commercialize a pelleted fertilizer made from cricket frass.

Located in Vineland Station, Ontario, Vineland considers itself a leader in the research and innovation of horticultural products and technologies.

Along with Aspire Food Group’s foray into using insects as a food group for human consumption, trendy TV chefs are using them with wild aplomb and not just for shock value. Many other companies in Canada have entered the insect-as-food sector.

While this writer had long ago munched on stewed inago (whole stewed, but crunchy grasshoppers) and hachi-no-ko (baby bees, aka bee larvae) in his years living in Japan—they were delicious—the insect as food craze remains two-fold for North American consumers.

Insects as food continue to be an oddity or “dare” for carnival eats and treats in such fare as scorpion lollipops or cockroach candy, or it’s found as a cricket powdered mixture secreted in grocery stores within the packaged organic foods section. There, usually in a stand-up, resealable pouch, the cricket powder is hailed more as a protein substitute for meat. It’s not, but it is chock-full of protein. And it didn’t taste much like anything, unlike the Japanese delicacies.

While North American consumers still struggle with their gag reflex when consuming insects, the US Department of Agriculture claims that the average person annually accidentally eats up to 1 lb. (453.6 grams) of flies, larvae, and other insects. People who wore masks during the COVID-19 pandemic and a full nose/mouth mask for their sleep apnea probably consumed less.

But those who farm insects still hope North American bug powder consumption will increase. Even if it doesn’t exist in North America, the protein substitute is expected to be better accepted by countries still considered “developing.”

Regardless, SureSource has, with the source materials from Aspire Food Group, enough of a cricket waste source that can be easily repurposed with the help of Vineland as a commercially viable fertilizer pellet source.

SureSource said that Kickin’ Frass would interest organic and greenhouse farmers. They noted that in trials, the frass-fertilizer-grown lettuce had higher chlorophyll concentrations.

While high levels of chlorophyll often indicate poor water quality, in the greenhouse with automated watering, this was a good thing, meaning that the plants were able to absorb easily with less work for the plant.

The company has indicated that because frass stimulates biological activity and nutrient cycling exceptionally well, the trials showed that the frass fertilizer produced the same yields as similar carbon-based fertilizers and soil amendments but at much lower application rates. In other words, Kickin’ Frass provided more for less.

SureSource said that Kickin’ Frass will initially be available as a dry crumble in bulk, in 1,000 kg/2,204 lb. totes and 25 kg/55 lb. bags. It also offers third-party custom blending and packaging.

Wait, what’s wrong with green ammonia?

Although the ag community may praise the Haber-Bosch process, which has for decades been a scientific method to produce ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen and has helped manufacturers create fertilizers, eco-warriors often decry the science as being responsible for 1.8 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions.

Back in the 1870s, farmers understood that adding ammonia and nitrate to the soil could increase their crop yields dramatically. Sodium nitrate was mined in South America for use as a nitrogen fertilizer. So high was its demand that just 20 years later, there was concern that the increased global demand would deplete the nitrate deposits.

Owing to those concerns and the fact that rival Great Britain (now the United Kingdom) held a stranglehold on the world’s nitrate supply, German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed the ammonia-making process in 1913.

Although the German war machine of WWI corrupted the process of creating nitrate explosives, after the war ended, the Haber-Bosch process was considered for agricultural purposes.

Despite all the good fertilizers have done for humankind, we still need to be mindful of the adverse effects of improper usage.

As CAAR members know, fertilizers have played a key role in boosting crop yields and providing security for North American food producers. The success of the fertilizer industry and the larger yields have also contributed to drawing more people to our breadbasket and growing our national population.

But with the good comes the environmental and climate challenges.

One solution—along with the cricket carcasses—has been touted as green ammonia. Green ammonia is hydrogen produced by electrolysis and powered by renewable energy sources. It is also called green hydrogen.

Using green ammonia/hydrogen will reduce carbon emissions in ammonia manufacturing, but it doesn’t do anything about the roots of carbon emissions.

As we know, after an ammonia-based fertilizer is applied to soil, the bacteria begin a nitrification process that converts the ammonia into nitrates. Nitric oxide, a GHG emission, is created as a by-product during this process.

Ammonia gas is also released into the atmosphere via the volatilization process, contributing to air pollution.

Some researchers are looking to move away from ammonia-based fertilizers and continue on the nitrate fertilizer path, but to do so more green and sustainably.

However, the solution to mining nitrate is lightning or a lab-created version.

Capturing Lightning in a Bottle

The world record for one person being struck by lightning at separate times is seven by Roy Sullivan, a US parks ranger who achieved the feat during his work hours between 1942 and 1977. All the strikes took place at Shenandoah National Park in Virginia.

The tiny hamlet of Harrow, Ontario, is considered the most lightning-affected place in Canada, with 35.9 days a year of lightning strikes based on a 10-year average. Of course, this data was from 2013, so we could have a crackling new winner.

Although we have talked about lightning as helping form the following fertilizer resource, we should confirm that it is simulated lightning. And it’s from the UK.

Debeye Ltd.—headquartered in Wiltshire, England, UK—has developed a modular and containerized system that uses air, water, and electricity to produce nitrate fertilizer.

Dr. Burak Karadag, Debye’s Chief Technical Officer, developed the technology. If creating such a technology sounds like rocket science, the truth is out there.

Once upon a time, Karaday was a space engineer working on satellite propulsion. After becoming interested in the properties of lightning, he wanted to see if he could combine space and lightning and do something with both on Earth, tackling one of the planet’s more significant challenges.

He knew that a thunderstorm’s lightning could produce enough electrical energy to separate the nitrogen atoms in the air. Once the particles are separated, they fall to the ground with rainwater. Combined with minerals in the soil, the fallen atoms formed into nitrates, a type of fertilizer.

For him, that was global food security. He acknowledged that fertilizer played a key role but that international politics can cause shortages. Also, there is the negative issue of GHG emissions.

The Debye proposition was that lightning hits water with enough energy to break it apart and create nitrogen dioxide, which is water-soluble and easily absorbed by plants.

Using locally, renewably powered direct nitrogen capture technology could make this fertilizer a near-zero-emission process.

Being able to produce it locally would also prevent global politics from limiting a country’s ability to obtain needed fertilizer resources.

Currently (no pun intended), Debye is working with the York, England, UK-headquartered Agri-Tech Centres on an 18-month trial basis to examine the feasibility of the simulated lightning fertilizer product concerning lettuce crops.

While the hope is that the applied lightning fertilizer will provide a similar yield to the contemporary fertilizers used by farmers, Debeye plans to give a greener resource.

Next, the company seeks to develop a one-kilowatt proof-of-concept prototype to quantify and compare crop yields and post-harvest properties for standard nitrogen fertilizer and fertilizer produced.

If commercial viability is determined, the next step would be undertaking small-scale pilot projects in a farm setting within three years, subject to funding.