Gene-editing, whether it is for crops or livestock, has long been a global hot-button topic within the ag world and beyond.

Some fear the so-called “Frankenstein-ing” of the foods people consume as being an affront to the public well-being, with some likening it to the failed eugenics movement of racial improvement of the early 20th century and/or planned breeding.

To be fair, the concept of planned breeding has gone on in the world of humanity since wolves were domesticated to become the breed of dogs we invite into our home.

The same holds true for how we breed swine, cattle—both dairy and beef—poultry, you name it, and the animals we consume on a daily basis are certainly different from how they appeared on the average North American farm 150 years ago.

Farmers have certainly done the same to crops. If you’ve eaten a banana within the past 50 years, chances are you aren’t eating the same banana prevalent on grocery shelves back in the 1950s.

By 1965, the Gros Michel species of banana was the banana of choice, but was wiped out by a disease, with a different but similar strain of fungal disease taking out the global commercial banana plantations. We now nosh on the Cavendish banana, but because the same disease that wiped out the Gros Michael—Panama Disease—is currently wreaking havoc on plantations around the world with fears it will hit South America, it has caused scientists to begin work on developing a hybrid version of the Cavendish and a Madagascan banana that they hope will resist the fungus.

Right now, the Madagascan banana is being described as being inedible with large seeds in the middle—but it is immune to the fungus. A simple cross-breeding exercise with a Cavendish would get us, hopefully, a banana that tastes half as good as what we eat now—which is apparently not as tasty as what we ate back in the 1950s.

Yes! We have no bananas. We have no bananas today. – Groucho Marx, Eddie Cantor, Louis Prima, etc.

But that’s not good enough. Scientists are looking to marry the Cavendish flavour with the fungal resistance—less the large seeds—to create a crop that future generations can enjoy on their breakfast cereal or as a potassium addition for those wanting to avoid dehydration after a heavy workout.

Could we one day have an orange more orange than an orange? Sure. And like its banana cousins, it’ll taste like an orange, too.

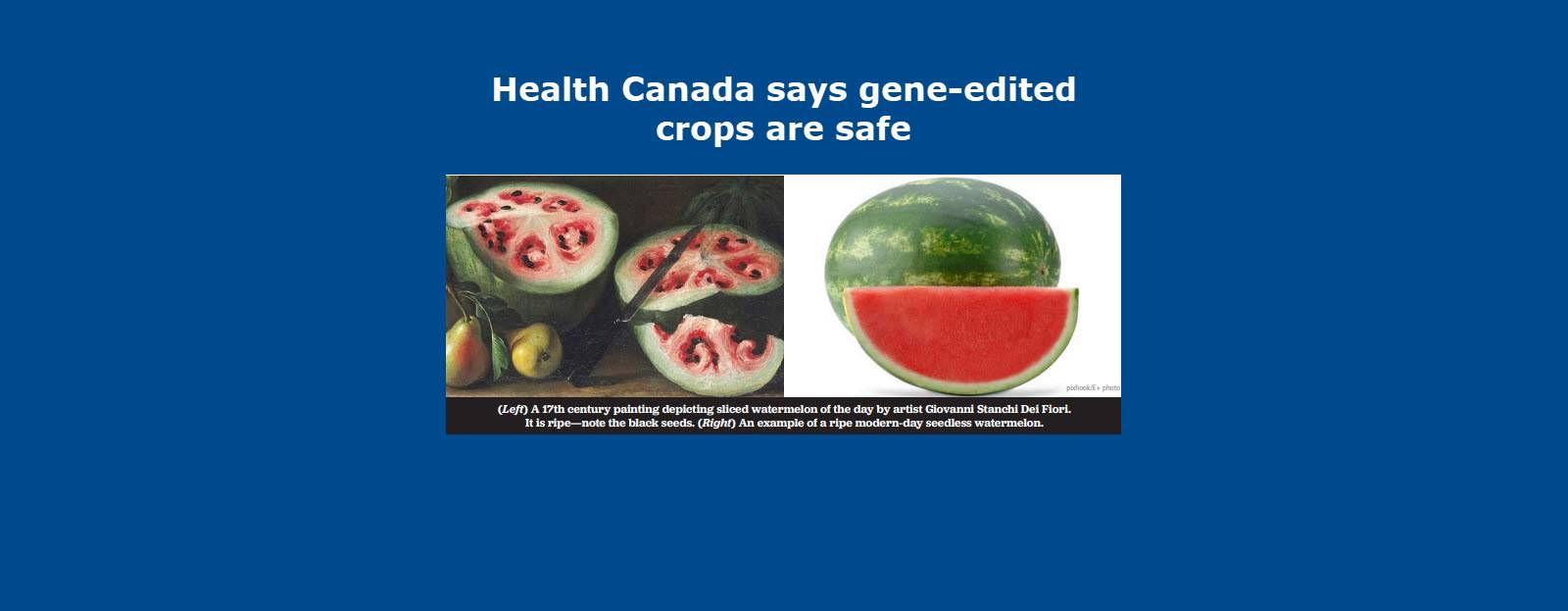

Hopefully we are all aware that the grown food we consume today looks nothing the way it did before man got his hands on it for successful cultivation.

Consider, if you will, that the beautiful corn on the cob produced by a local farmer or watermelon you just bit into with its juicy sweetness running down your chin didn’t always look or taste the way it did in the past. The same holds true for wheat, aubergines, carrots, peaches, etc.

Canada’s modern ag industry owes a great deal to genetics. And the same holds true for the creation of modern pesticides, fungicides, et al.

First domesticated from the teosinte plant—a plant native to Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua—some 6,000 years ago, this nearly inedible plant would be the forefather of modern sweet corn. Our modern corn—depending on the harvest—can be 1,000 times larger, easier to peel and grow, and per the Encyclopedia Britannica, is made up of 6.6 percent sugar versus 1.9 percent in natural corn. These changes, it is surmised, occurred after the 15th century during the European invasion of the indigenous peoples of North America.

It may not have involved gene-editing, but it certainly involved genetics.

While genetically modified foods may garner a strong negative reaction from some, humans have been tweaking the genetics of our consumable foods for thousands of year—The Simpsons whimsical tomacco notwithstanding, when Homer Simpson mixed tobacco and tomato seeds in the ground and embedded plutonium rods to give them a healthy(?) green glow to grow overnight into an addictive and delicious hybrid crop.

Genetically-speaking, while tweaking genetics of foods is a slow process, genetic modification and gene editing are done, relatively-speaking, extremely quickly.

Genetic modification may involve splicing in genes from a bacteria to provide a resistance to pests, while gene editing is a scientist manipulating the DNA in a plant, for example, to provide it with better pest resistance.

Under differing circumstances, farmers have always sought to combine the best of different types of a fruit or vegetable to create a bigger, better, hardier, and tastier crop (though not always tastier) that can make it to market safely for human consumption.

The formal clarification of crossbreeding plants and animals (though not the two together), could provide farmers with a superior crop or herd, arose between 1856-1863 when Gregor Johann Mendel, and Augustine friar and Abbot of St. Thomas’ Abbey (now in the Czech Republic), experimented with pea plants, establishing the rules of heredity, aka the laws of Mendelian Inheritance.

Earlier this year, Health Canada clarified its stance on gene-edited crops—which is different from the aforementioned genetics.

“It’s a positive outcome that we’ve been looking forward to,” explained Dean Dias, Chief Executive Officer of Cereals Canada to Farms.com in a recent interview with writer Diego Flaminni.

Dias continued: “In Canada it’s not the technology that’s regulated, it’s the product. With gene editing, you’re not bringing in another trait from another organism, you’re just speeding up the process of what the plant would do with conventional breeding.”

The new guidelines offer opportunities for Canadian plant breeders because Health Canada explained that gene-edited crops should be treated like conventional crops and thus do not require pre-market safety evaluations.

Originally released in 1999, Canada’s Novel Food Regulations stated that a manufacturer was required to file a pre-market notification and for the regulator to determine that the information in that notification establishes that the food is safe before it can be sold.

The scope of these requirements is delineated by the definition “novel food” in these regulations. When a food is “novel” the regulations require pre-market notification and regulatory approval before sale.

But what is novel? Health Canada provided its Guidelines for the Safety Assessment of Novel Foods in 2006 as a means to aid in the interpretation of the Novel Food Regulations—yes, seven years later.

The 2006 guidelines better explained how regulators conduct novel food pre-market safety assessments and the information that must be contained within a notification.

Any fan of modern crime scene investigation knows that in 2006 DNA analysis took weeks to perform while nowadays rapid DNA testing can net results in as little as 90 minutes. The point is that technology has evolved over the years.

Since 2006 and Health Canada’s initial guidelines response, technological advancements have created new tools of genetic modification by which new plant varieties can be developed (e.g., gene editing technologies).

As such, on May 18, 2022, Health Canada has provided updated guidance regarding the nation’s Novel Food Regulations—clearer, more predictable, and more transparent regarding products of plant breeding, including those developed using these new tools of modification.

According to Health Canada, “the new guidance takes account of the health and safety objectives of the regulations, making use of the regulator’s experience as this field of science has evolved since the regulations were published. This new guidance interprets the Novel Food Regulations in a manner that takes account of the current scientific knowledge and the underlying scheme and the purpose of these rules (i.e., to require pre-market assessment of novel foods that may pose a potential risk to the consumer) in a way that reflects a greater understanding of plant breeding technologies, and the benefits of aligning with our international regulatory partners.”

First, the Novel Food Regulations are product-based, based on the characteristics of the product, and are NOT based on the process by which the product is developed.

For Health Canada, its approach is to determine whether a product may contain an allergen or toxin—to provide a determination if the product is safe for consumption.

Health Canada said that the presence of foreign DNA is part of its five categories of characteristics that a plant may have that would require it to undergo a safety assessment before its use in the Canadian food supply.

But with its recent clarification, it doesn’t matter if a plant was developed via conventional breeding, or gene editing.

Gene-edited crops can be treated like conventional crops, and don’t require pre-market safety evaluations. However, genetically modified crops do (still) require a safety evaluation.

These safety evaluations are in-depth, and can involve a multi-year process before a decision is made one way or the other.

CropLife Canada was pleased with the clarification to the Regulations, and noted via a statement: “Clear, predictable and science-based policies support investment in innovation in Canada, which will help drive greater agricultural sustainability and productivity while helping address the challenges of climate change and global food security.”

Within In the geopolitical global spectrum, the Health Canada decision now aligns Canada with the same stance on gene-editing as many of its main trading partners, including the US, Japan, Argentina, and Australia.

“This is great news for Canadian plant breeders, but we have a lot more work to do with our trading partners to make sure we don’t have any market access concerns,” continued Dias. “Some importers may have restrictions, so we’ll need to have those conversations to provide clarity to our customers around the world about where Canada stands.”

The Health Canada announcement positions itself around a 2021 poll that found that over 80 percent of Canadians queried did support gene editing—if it led to disease-resistant crops and/or a reduction in pesticide usage.

Regardless of the views of the 80 percent in favour of gene editing, and the backing of Health Canada, and it now playing on the same level playing field as many of its trade partners, one can not please everyone.

One such entity is the Canadian Biotechnology Action Network (CBAN). CBAN, headquartered in Ottawa, is a charity group consisting of 15 groups in an effort to research, monitor and raise awareness about negative issues relating to genetic engineering in food and farming.

It’s member groups include the Canadian Organic Growers, National Farmers Union, and the Ecological Farmers of Ontario—all of whom oppose the new Health Canada regulations.

CBAN, along with the Quebec network Vigilance OGM (GM Watch), are very concerned that Health Canada is allowing product developers to assess the safety of many new gene-edited foods (those with no foreign DNA) with no role for Health Canada regulators.

They state that the Regulatory guidance will also limit the government’s powers to simply asking companies to voluntarily notify the government of new gene-edited foods coming to market.

Lucy Sharatt, a Coordinator with CBAN expressed the entity’s moral outrage in a released statement.

“We’re shocked that the Minister of Health has committed to corporate self-regulation of these gene-edited foods. Canadians will soon be eating some gene-edited foods that have not gone through any independent government safety checks, and some of these foods may not even be reported by companies to the government or public,” stated Sharratt. “This decision profoundly increases corporate control over our food system.”

CBAN claimed that Health Canada has essentially removed itself from doing its job, and that without this authority, the federal government cannot obtain the necessary information from companies about these food, and thus limit itself to knowing everything it should about gene-edited foods making its way to market.

Whether or not one agrees with the CBAN stance, Health Canada has announced a voluntary “transparency initiative” which it asks companies to voluntarily notify it of unregulated gene-edited foods coming to market.

Health Canada stated: “All food producers are responsible for ensuring they comply with the provisions of the Food and Drugs Act and its regulations. This responsibility includes determining if their products meet the definition of a “novel food” and submitting a notification for pre-market assessment to Health Canada prior to sale in Canada.

“Health Canada’s new guidance doesn’t change this responsibility.

“Health Canada will continue to encourage developers to request a novelty determination in cases where they’re unsure of the regulatory status of their products.”

Health Canada said it realizes there are certain products of plant breeding that don’t meet the definition of a novel food, such as foods produced from specific GM plants—depending on the characteristics expressed by those plants.

Unfortunately, Health Canada admitted that it lacks the regulatory authority to require notification of products that are not novel. It is voluntary.

Lacking that authority, Health Canada is, itself, hamstrung.

As a means to provide some transparency, with regards to the non-novel products, Health Canada maintains a list of products, since 2012, where the producer has sought confirmation regarding the novel food status.

Again, the list is compiled as companies seek confirmation regarding its products’ status. Voluntary.

Despite its oft-limited authority regarding some issues, Health Canada is still a science-based agency.

It examines all available scientific literature regarding the use of gene editing technologies in plant breeding.

It also reviews expert opinions from industry, academia, and government sources.

It’s why Health Canada is confident to state that there is a consensus regarding gene editing technologies, that it presents no “unique safety concerns compared to other more conventional methods of plant breeding.

In its concluding remarks, Health Canada said: “The identification, characterization, and management of public health risks from food functions best when the focus of regulatory programs is on the final characteristics of products rather than the technologies used to make those products.

“The reason for this is that for a hazard to present a public health risk, the public must be exposed to the hazard. As is the case of chemical and physical mutagens used in plant development, so is the case of rDNA and gene editing technologies in regards to food safety. In none of these cases are people typically exposed to these technologies through food, rather it is the final characteristics of the food to which consumers are exposed.

“Furthermore, while plant breeding has advanced significantly over the last two centuries, the basic plant breeding technologies of crossing and selection are still applied, even for products of rDNA and gene editing technologies. This matters in regards to managing food safety risks because conventional plant breeding technologies, like crossing and selection, are used to select against undesirable characteristics that could result in food safety risks. In rare instances where the undesirable characteristics cannot be eliminated due to genetic linkage or other confounding reasons, plant developers have a history of removing such products from further development altogether, thereby supporting food safety.

“As such, it is the scientific opinion of Health Canada that gene editing technologies do not present any unique or specifically identifiable food safety concerns as compared to other technologies of plant development.

“Therefore, gene-edited plant products should be regulated like all other products of plant breeding within the Novel Food Regulations (i.e., by the characteristics they exhibit and how these characteristics impact food safety).”

In other words, Health Canada will regulate gene-edited products of plant breeding in the same manner as all other types of bred plants.