A look at the four primary modes of transportation—their pluses and minuses.

By Andrew Joseph, Editor

In Canada, our agricultural community has often been up in arms about the service it has received from the duopoly that is Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway.

It’s not from the transporting of the ag products that the complaints come, but rather from the lateness of the hopper cars and often just not enough cars being sent—both of which cost farmers and traders much money with buyers and a loss of face globally on the economic market of reliability.

This past season, the Canadian Pacific and Canadian National railroad companies showed that they had put their money where their proverbial mouth was and worked hard to provide the Canadian agricultural landscape with a more reliable mode of transportation.

And yet, despite the hard work and promises, many in the ag industry felt the railroads’ inability to deliver in their pocketbooks.

So why is it that we rely so heavily on railroads to ship our products?

Statistics Canada said that in 2017, 90 percent of the 72.9 million freight shipments in Canada—ag and other market segment goods—were hauled by truck.

Transporting by rail only accounted for nine percent of Canada’s freight shipments in 2017, with air accounting for the rest.

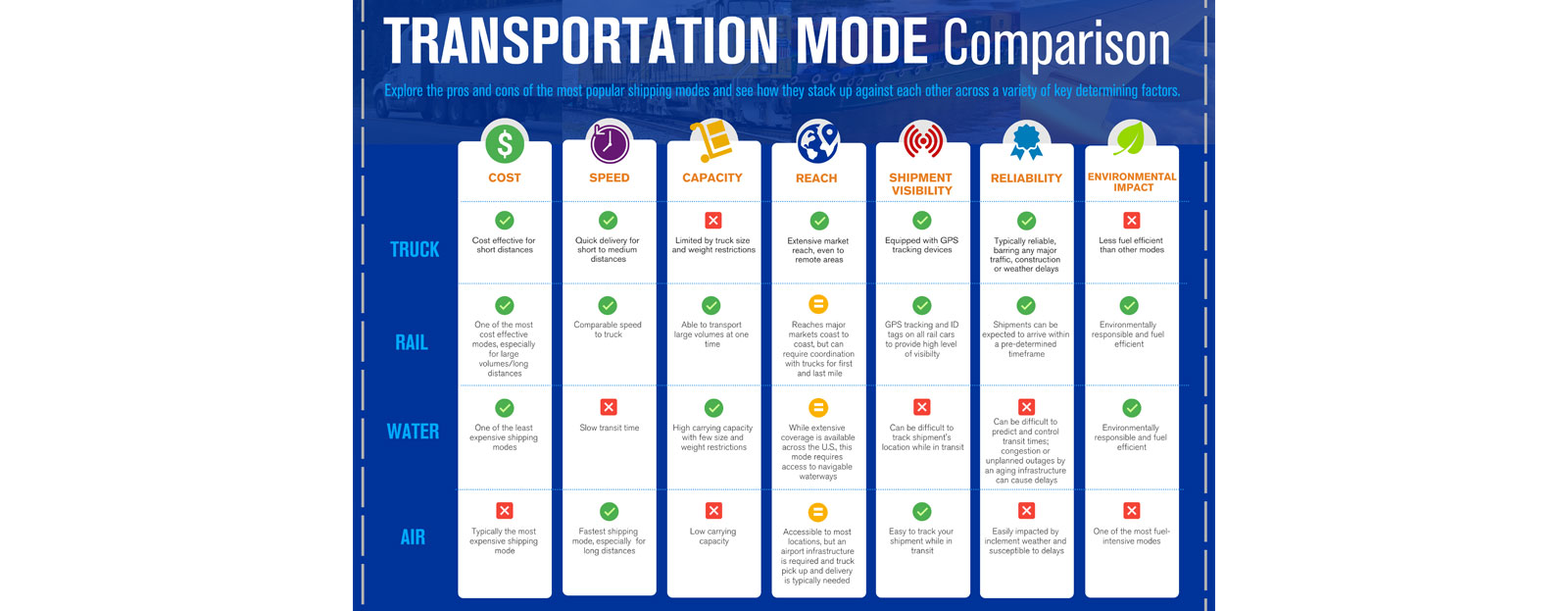

However, there are four different modes of freight shipment: 1) truck; 2) rail; 3) air; 4) water.

Let’s look at all four modes of transportation and examine why we use them and why we don’t.

Barging In

We’re unsure why the StatsCan number did not consider water as a freight or goods transportation mode, considering it has a high carrying capacity and few size and weight restrictions.

Water transportation is also a very environmentally responsible method, not to mention fuel-efficient.

Oh, and it’s also a relatively inexpensive mode of transport, with a low dollar-per-ton-per-mile ratio. So why isn’t it being used more by agriculture?

Well, there are possible extra costs for warehousing fees—an expensive proposition if the freight has to sit for a while.

But extra storage costs are always a possibility for any mode of shipping.

As we’ve seen from railroads not always being able to deliver crops on time, time is money.

The biggest drawback of water transport is its slow transit time. That, and not every part of the country is physically connected by a waterway—unless we want to construct our Canadian version of a Panama Canal bisecting the country.

Speed, or rather, the lack of it, is a factor. Ships and barges travel at a rate of five to 11 miles per hour (eight to ~18 kilometres per hour) on inland routes such as the St. Lawrence or Mississippi rivers, but up to 20 mph (32 kph) on the open seas or oceans.

Depending on the destination, shipments can take up to a month to arrive, but they can be further delayed owing to port congestion surrounding aging infrastructure. And, so it is said, it can be challenging to track a shipment while in transit—but we don’t believe that for an instant.

Although tracking a ship on water may be true in some less-than-legal instances, for shipments originating in the US and Canada, it is easy enough to know exactly where a ship is along any given waterway—whether en route or in port.

Products such as grain, minerals, metals, ores, steel coils, and heavy machinery are all goods best served by a water transport method because of the size or volume of the shipment.

Of course, since such waterways as the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi serve Canada and the US, the product must be transported to ports along these rivers by either rail or truck. So it’s not as though we don’t use water as a method of transportation. We do, especially when the ag product goes to countries outside Canada, Mexico, and the US.

In Canada, grain storage co-ops often have a spur line back onto a main train line or multiple filling areas for trucks to move the product to a port.

The Air Up There

While an option—an expensive one—the Canadian ag industry does not rely much on air to transport goods from Canada to customers.

However, floral breeders will use high-volume cargo planes to transport living plant material from foreign locales to Canadian breeders.

Selecta is a poinsettia breeder that distributes the plants through the North American market via the Ball Horticultural Company.

In mid-June, farms in Mexico, Nicaragua, and Uganda begin to ship cuttings of poinsettia to breeders in North America, ensuring the shipment is sent at an adequately maintained temperature.

After these cuttings are grown at the Canadian and US breeder facilities, the poinsettia plants are shipped via truck in mid-October to florists et al.

Often, large volumes of live products, such as flowers and aquarium fish, are shipped by quicker airplane transport to ensure a higher survival rate.

However, the cost is high—air freight is often 20 times more expensive than other modes of transport.

And if you are looking for a small carbon footprint, look elsewhere. Air transport costs in dollars and GHG emissions are high for jet fuel, maintenance, labour, and landing fees.

But, as noted, perishable items can be moved and received in 24 to 48 hours, so customers can place orders on demand, which provides a reduced lead time and savings on inventory and storage costs.

Also, products shipped by air are easy to track while in transit; however, after a $20 million gold shipment was stolen at Pearson International Airport in Toronto this past March, security is an issue on the ground.

Similarly, in 1952, what was then Canada’s most significant gold theft occurred at Malton Airport (now Pearson.) It remains unresolved.

Along with its higher cost and being less environmentally friendly than other modes, air transport can be negatively impacted by inclement weather.

Then there’s the low carrying capacity and a lack of door-to-door capabilities.

But, on the plus side, you can reach any place in the world with a delivery, especially with smaller aircraft and those with water landing capabilities.

Train Spotting

It is well-established that railway is one of the most cost-efficient methods for shipping large volumes of goods over long distances.

It has a lower cost per ton per mile than trucking, in which trains need less energy to move goods than a truck while still carrying the equivalent of 300 trucks.

Speed—trucks and trains are equivalent—but trains don’t have traffic jams. Usually.

While the weather can impact the reliability of rail usage—line washouts or it’s too cold to run—rail is the most environmentally responsible of all four transportation types.

A railroad can move one ton of freight a total of 500 miles on one gallon of fuel, with trains being four times more energy efficient than trucks (according to Union Pacific Railway). Want more? How about the fact that freight railroads only account for 0.6 percent of all GHG gas emissions and two percent of all transportation-related emissions in the US, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency?

While the biggest drawback to train usage is that rails do not run everywhere, it means that the product often has to be trucked to a train loading area—but that’s okay.

Thanks to the many railroad tracks laid across the US and Canada, it enables it to reach the major markets from coast to coast in both countries.

It can now easily reach a third country—Mexico. This past March, Canadian Pacific acquired Kansas City Southern for US$31 billion in a deal that included its subsidiary, Kansas City Southern Mexico. The railroad merger is known as the CPKC.

For the Canadian ag community, this critical merger will allow grain from the Canadian Midwest to move along the US Gulf Coast down into Mexico. Of course, it also makes shipping goods from Mexico into the US and Canada more accessible—though only to the left coast.

And if Canadian Pacific’s merger sounds like a brilliant way to open up railroad routes for the three countries, note that its triple-country monopoly was only able to last a couple of months, as Canadian National also decided to make a play.

To counter—or instead, in response to—the recent CPKC railroad merger, three other railroads—one each in the US, Mexico, and Canada—joined forces.

Known as the Falcon Premium intermodal service, the Canadian National, Union Pacific, and Grupo Mexico railroads have allied themselves to ship goods between the three countries.

Reports indicate that the Falcon Premium will dip into Mexico via Grupo Mexico railway’s hubs in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, and Silao, Guanajuato, and enter the US via Eagle Pass, Texas.

From that US point, the Union Pacific railway lines will be followed up into Chicago, Illinois, and Detroit, Michigan, where, from the Motor City, goods and freight will then be able to enter Canada.

Via the Canadian National eastbound railway network, goods can move east through Toronto, Montreal, and Moncton, ending at Halifax.

To the west, from its Chicago hub, the Falcon Premium trains will move through Winnipeg, Regina, Saskatoon, Edmonton (with a spur line to Calgary), and then into British Columbia, where they split into two hubs—Vancouver to the south and Prince George to the north.

The Falcon Premium venture allows everything from food, appliances, auto parts, and more to move from Canada’s east and west coasts into the US and Mexico, if necessary, and vice versa.

According to a phone call to investors on April 24, 2023, the Canadian National, Union Pacific, and Grupo Mexico representatives said their service would be better than CPKCS because Falcon Premium has a more extensive network in Mexico and because it has Union Pacific’s direct route to the Chicago hub—long considered a central hub of the US and North America.

Regardless of the “fighting words” from Falcon Premium, both it and CPKCS are hopeful that their rail service will encourage more customer usage over the less fuel-efficient truck transport fleets—at least until that not-yet-developed technology allows road vehicles to travel farther without having to stop often for refueling or recharging.

Keep Truckin’ On

Trucking has been a viable method of moving goods across Canada for 125 years, since 1898, when Robert Simpson Company Limited in Toronto used the first commercial truck in Ontario as a delivery wagon for the department store’s wide variety of goods.

Trucking continues to be the most common mode of transportation in the US and Canada, and it is the quickest way to deliver products on short hauls.

There are only two significant drawbacks to trucking over other modes of transportation: a lack of fuel efficiency and a limitation on the amount of freight that can be moved in a single trip.

Of course, there are also weather impacts, poor traffic conditions, and driver hour limitations—though tandem drivers can alleviate those.

The odds are, even when using other modes of transportation—air, ship, or rail—the trucking industry was probably involved in that last-mile delivery from, say, a farm to a port or from a port to a retail centre.

And why not? As long as there’s a road, a truck can use it.

Trucking is considered an affordable short-haul option for agriculture and other industries.

It’s why, even with the negative drawback of GHG emissions caused by diesel-powered big rigs, it doesn’t mean it’s not the best alternative over shorter distances.

Over short- and medium-haul distances, trucks featuring alternate power sources such as battery electric and hydrogen-hybrid trucks are available—meaning sustainability concerns need not be a “concern.”

Pros: cost-effective for shipping freight short distances; provides door-to-door pickup and delivery; and has an extensive market reach, even to remote areas.

The lack of GHG emissions from alternate fuel-source trucks helps save the environment.

Still, regardless of the vehicle’s power source, all trucks have rolling resistance and air friction working against them, both of which lead to high fuel consumption—higher than all except for air transport.

Even that may change as vehicles begin to see technological advances using regenerative braking to use the power of a vehicle’s braking to store the kinetic energy and reuse it as a battery charge to add power to the electric batteries—thereby extending the vehicle’s range.

Trucks travel fast enough—you’ve probably seen them try to pass each other on a two-lane highway, each doing 110 kph—so we know trucks offer quick delivery for short to medium distances.

And, even with all the complaints about driving through a city core—trucks could drive around it—trucks are excellent at delivering freight on time as requested.

Although it’s a rare occurrence, truck theft can be a concern. Although trucks are easily tracked via GPS, crooks sometimes feel the need to try and outwit the law.

In October 2022, two people were arrested after the RCMP successfully spiked the road to stop a grain truck involved in a canola theft from a farm in the Bashaw, Alberta, area.

The more considerable drawback is the limit on the size and weight of the shipment versus the truck’s capacity—oh, and there are also government weight restrictions for loads. Still, when trucks are combined with rail, the agricultural community achieves an efficient and cost-effective shipping solution.

Related Articles

- April 2024 issue of CAAR Communicator now available online The April issue of CAAR Communicator "I Think therefore AI AG" should arrive in your mailbox any day now. The issue welcomes new Executive Director Myrna Grahn who began her new role on March 25, 2024. The featur...

- AI & Ag A viewpoint on how artificial intelligence can positively impact the agricultural sector. By Andrew Joseph, Editor When it comes to AI, aka artificial intelligence, people either know all about it or they don’t. ...

- Canadian fertilizer and the new insect and lightning alternatives Could lightning-derived technology or cricket frass be a new fertilizer option for manufacturers? By Andrew Joseph, Editor It’s spring, a time when crop farmers and retailers think profoundly about fertilizer—the...

- Myrna Grahn is our new Executive Director We are excited to announce the appointment of Myrna Grahn as the new Executive Director of the Canadian Association of Agri-Retailers (CAAR). She stepped into her new role as of March 25, 2024. Myrna brings a wea...

- Increasing your company’s brand reputation A well-thought-out brand marketing campaign will help you grow and promote your brand. By Andrew Joseph, Editor A company is often only as good as how the customer or consumer perceives it to be. It doesn’t even...

Join the discussion...

You must be logged in as a CAAR member to comment.

Report

My comments